The Old Man & the sea

In what I consider a good omen for the recent release of my book “Ocean Titans” here in Canada, I received an email from “the Old Man” this past week. It was sent from somewhere off the east coast of Nova Scotia, from a merchant ship plodding its way south towards Jacksonville, Florida. Sounded like the trip could be a little rough: as he wrote, “The weather isn’t too good, but the vessel is okay. We say ‘brave’.”

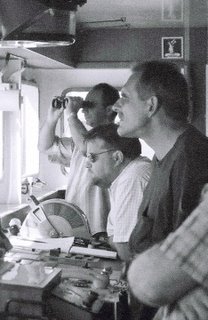

The “Old Man” in question is Captain Jacek Wisniewski, a Polish mariner I first encountered aboard the bulk carrier MV Antwerpen about a year and a half ago, when I joined him and his crew for my first extended trip to sea with a commercial vessel. Captain Wisniewski is now in charge of the MV Gdynia, a new vessel that he will call home for the next four months.

Though his official title is Master Mariner, most of us know him as “the Captain”. Except, that is, his crew, who have another term to describe the individual legally in charge of a vessel, its cargo and anyone who sets foot on its decks. To those who work on commercial vessels, the person who safeguards their lives at sea is universally known as “the Old Man”. This is not a slight at their age nor a reflection on any curmudgeonly aspect of their character, but an honorific steeped in tradition, something whispered behind his back. (Captain Wisniewski is himself in his early forties and an intelligent and cultured man with a wry sense of humour.)

There are perhaps 50,000 individuals worldwide who bear the credentials necessary to command a merchant ship. The vast majority are, in fact, men, though a few women continue to make inroads into this somewhat exclusive fraternity. And even they may be referred to as the Old Man by their crews.

To be a Master Mariner is to reach the pinnacle of professional seafaring. It takes decades to become one and entails taking on responsibilities well beyond the scope of what most of us bear. In an era in which accepting responsibility for one’s own actions seems out of vogue, the captain of a sea-going vessel shoulders ultimate and direct responsibility for everything that occurs on his watch. And, yes, they can still perform marriages at sea.

I again thought about the responsibilities captains take on when I read Wisniewski’s email, heading into rough seas with a multi-million dollar ship, a crew of about thirty and a heavily insured cargo. Would most of us do what he does? Not likely.

Consider this scenario: You are driving down the road in your car, a vehicle that has been certified as safe; you have years of experience driving and you haven’t been drinking. The weather’s clear, but suddenly you spy another car veering into your lane, straight at you. You steer out of the way to avoid a head-on collision, but managed to scratch a rusty trailer parked nearby. As a result, you are charged with negligence and must accept at least part of the responsibility for other driver’s incompetence. Would you accept that? Not damn likely.

Yet that is the fate of master mariners. An abiding principle of seafaring is to avoid a collision – with another vessel or dry land – at all costs. The safety of the ship and its neighbours is a priority.

This, of course, also extends to aiding those in need, so long as it doesn’t endanger one’s own crew. I think about another Old Man I sailed with, Captain A.S. Grewal of the container ship MV Canmar Spirit. I spent a couple of weeks with Captain Grewal and his crew crossing the North Atlantic, not long after first meeting Captain Wisniewski.

We had a very tumultuous crossing that time. This is not merely a writer’s perspective, but a reality: at least one ship sank on the oceans we were transiting that time and a couple of experienced mariners later told me it was one of the worst set of conditions they’d seen in a while.

After disembarking from Captain Grewal’s ship in Montréal, the ship returned across the North Atlantic to England, encountering a vessel in distress southeast of Iceland. To his credit – and that of his crew – Captain Grewal responded to the S.O.S. and successfully rescued the sailor from his wallowing boat, upholding a tradition that goes back thousands of years, the one that promises to do whatever humanly possible to protect a life at peril on the seas.

To Captain Grewal, Captain Wisniewski and all the other mariners who are willing to brave the elements in defence of others, I thank-you.